Libraries, often unifying spaces, increasingly offer public classes on nutrition literacy, food security, and how to get a good meal on the table.

Libraries, often unifying spaces, increasingly offer public classes on nutrition literacy, food security, and how to get a good meal on the table.

August 27, 2025

The Free Library of Philadelphia Culinary Literacy Center offers more than 30 culinary programs for adults and children, including cooking classes with local chefs. The center has become a culinary model for libraries around the nation. (Photo credit: Elizabeth Marshak)

For the last five years, Michelle Coleman has attended cooking and culinary education classes in a light-filled teaching kitchen at her local library in Boston. The kitchen, designed for hands-on cooking and demonstrations with four gas cooktops and a 17-foot-long counter, was included in the building’s redesign in 2020 in response to community feedback.

Expand your understanding of food systems as a Civil Eats member. Enjoy unlimited access to our groundbreaking reporting, engage with experts, and connect with a community of changemakers.

Already a member?

Login

Here Coleman learned how to compost and repurpose leftovers, thereby reducing her food waste, a bonus to learning about new foods and flavor profiles.

“Cooking in public spaces is really fun,” says Coleman, a retired academic medicine administrator who owns over 300 cookbooks. She enjoys combining her love of cooking with being social. “The library has become this much broader social space for people to feel supported and in community.”

The Schuylerville Library in Schuylerville, New York, features a community fridge. (Photo courtesy of Farm-2-Library)

Across the country, libraries are using culinary programs to evolve beyond traditional book-lending, adapt to users’ needs, and reshape themselves into contemporary centers of community. Events have generally centered on cookbook or food memoir discussions, perhaps sharing dishes connected to the title, but libraries are increasingly expanding this concept.

For example, some libraries in New York’s Hudson Valley are hosting cider and cheese tastings in a nod to the area’s prolific agricultural scene and experimenting with family-friendly supper clubs. Many are offering programs that help people fight food insecurity and learn wellness and life skills.

Others may give out seeds and spices, lend out kitchen equipment, or host free pantries or grocery stores.

These efforts come amid the declining use of libraries, which are also facing attacks from conservative groups seeking to ban books and even defund libraries. Regular library visits nationwide decreased by 46.5 percent between 2019 and 2022, according to the 2022 Institute of Museum and Library Services’ Public Library Survey. However, recent data shows an upswing as branches reconsider their roles and communities’ needs.

“The reason that people come into their libraries changes, and it’s different and unique to the community that’s being served,” says American Library Association President Sam Helmick. “We should always be asking who’s not at the table and inviting them [in].”

Elizabeth Marshak is the assistant head of the Free Library of Philadelphia Culinary Literacy Center, which in 2014 pioneered the idea of using cooking in a library to develop knowledge and competencies within the Philadelphia community.

You need literacy to cook, she says. “You’re reading the recipe or following directions, gathering your ingredients. There’s organization, a lot of different skills that get improved by cooking,” she notes.

The Culinary Literacy Center features a well-stocked commercial kitchen with seating for 35, a demonstration kitchen, classroom space, prep space, a walk-in refrigerator, and a dishwashing room. It has three Charlie Carts, mobile electric kitchens inspired by the iconic cowboy chuckwagon. The center also has three toolboxes with electric skillets, cutting boards, and other small kitchen tools that are deployed to library branches for simple cooking programs.

Every month, the center offers more than 30 programs for adults and children, from nutrition education to cooking with a local chef, funded by the library, grants, and the center’s rental revenue. Since 2015, the center has also offered Edible Alphabet, a free eight-week, English-language learning program that began as a way to help refugee women in Philadelphia find community. The program is now available to anyone who wants to learn English.

The Pember Library in Granville, New York, offers a variety of cooking workshops, including this one on canning. (Photo courtesy of Farm-2-Library)

The center has become a model for libraries around the nation, including for the Boston Public Library’s Nutrition Literacy program, where Coleman takes classes. Stephanie Chace, who runs the Boston program, says its events reflect a belief that nutritional literacy should include a cultural understanding of food. The lab hosts ayurvedic wellness cooking workshops for new mothers and multi-series offerings like “Navigating Diabetes Through Food and Community.”

The latter, a one-time only course, combined medical professionals, nutritionists, movement specialists, and discussions about African diaspora and African food with renowned culinary historian Dr. Jessica B. Harris.

“I think people feel understood by the library when these programs are offered,” Chace says, adding that this encourages them to return.

The Nutrition Literacy program also features a chef in residence, who researches food topics and creates recipes and classes around them. The current resident is Kayla Tabb, a pastry chef and recipe developer who is studying Indigenous shoreline foods of Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

Through an anonymous $500,000 grant, the program is growing, with additional staffing and a pilot program of five mobile kitchen kits. They consist of easily transportable equipment like induction cooktops and blenders and can be requested by a branch librarian.

Across the country, libraries have long been trusted, accessible, and free repositories of resources and information, a democratized space for all. Library administrators look to see what a community needs or lacks “and how we can solve these problems,” says Jack Scott, outreach consultant for the Southern Adirondack Library System in New York.

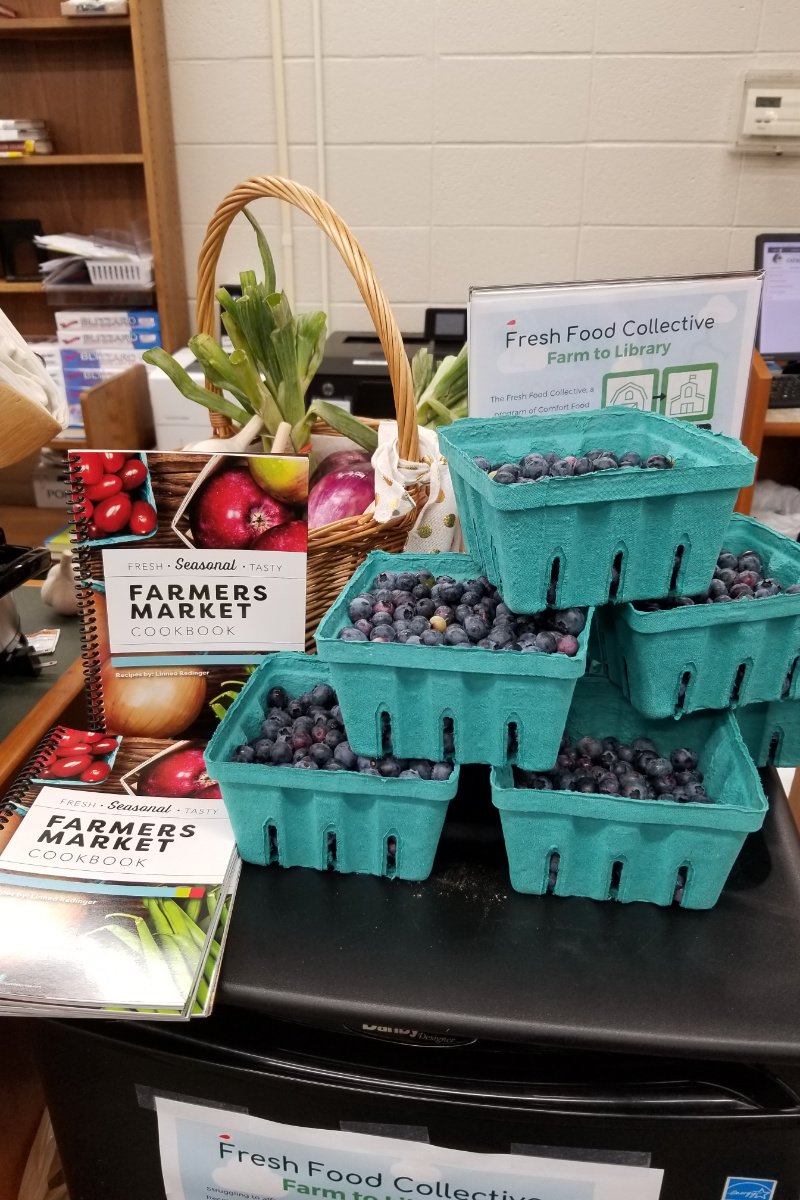

He oversees Farm-2-Library, which delivers rescued food to 13 libraries for locals to pick up, helping solve problems with food distribution in this rural region.

At the Terrytown Library outside New Orleans, culinary education has blossomed into two weekly children’s cooking classes serving 48 kids, adult culinary and nutrition classes, and a community teaching garden that produces vegetables, fruits, herbs, and flowers.

In the four years since the library began offering culinary education, branch visitation has increased, and physical circulation of materials such as books, DVDs, magazines, and the Library of Things collection has jumped 9.5 percent, says Bethany Lopreste, the library’s manager. The Library of Things allows patrons to sign out items used in daily living, such as kitchen equipment or home improvement tools.

Programs like these help people make proactive choices in their own lives, she added.

“Teaching someone how to cook, how to garden, and how to encourage and include their families to participate is really impactful.”

“Teaching someone how to cook, how to garden, and how to encourage and include their families to participate is really impactful,” Lopreste says.

Learning cooking and self-expression in a safe space are “life skills they can take forward with them,” says Athena Riesenberg, who runs a popular teen cooking program at the Des Moines Public Library’s Franklin branch. During National Poetry Month, for example, attendees baked fortune cookies and wrote their own fortunes. Riesenberg saw how the program fostered camaraderie among participants, one of whom is heading to culinary school after high school.

The Central Arkansas Library System, whose motto is “The Library, Rewritten,” views the library’s role as a community wellness and information hub. Librarians there are information specialists for the community’s day-to-day needs, explains Jessica Frazier-Emerson, coordinator of Be Mighty, an anti-hunger program serving 14 libraries in Little Rock.

According to the Public Library Association’s 2022 services survey, 31.6 percent of libraries say food insecurity is a need they currently address.

“Libraries are accessible, which makes them ideal for food and resource distribution,” Frazier-Emerson says. “They are also bound to only offer no cost and identification-free programming, which also lends to equitable food distribution.”

The Be Mighty program provides after-school and summer meals for children through the U.S. Department of Agriculture, application and interview assistance for public benefits such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), community refrigerators, little free pantries, nutrition and trauma-informed cooking classes, and free monthly bus passes.

With the recent federal cuts to SNAP benefits, however, Frazier-Emerson worries that she may have to reduce the number of branches that Be Mighty serves.

Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill didn’t cut funding to the Child and Adult Care Food Program or the SUN Meals, which supply meals to the Be Mighty sites, but Frazier-Emerson is unsure the programs will remain unscathed.

SNAP-Ed, a federal grant program that teaches SNAP recipients how to stretch their SNAP dollars and cook healthy meals, has had its funding eliminated. SNAP-Ed supported some Be Mighty partners, including Arkansas Hunger Relief Alliance, so Be Mighty now offers fewer offsite cooking and nutrition classes.

There are no provisions in the federal bill that directly affect library funding nationally, but the burden it adds on state and local governments imperils support for libraries and other essential infrastructure. Separately, though, the federal government withheld funding earlier this year from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), which funnels money to state libraries to use and distribute. And the greater concern is for 2026—when IMLS may be eliminated.

The Schuylerville Library in Schuylerville, New York, regularly distributes fresh fruit and cookbooks. (Photo courtesy of Farm-2-Library)

As a result, the New York State Library anticipates losing $8.1 million. At the Southern Adirondack Library System, operations could be crippled, since the funding supports 55 of 80 jobs, including those responsible for processing construction grants, Scott says. Many projects could remain incomplete.

In Arkansas, smaller libraries will feel the greatest impact because they won’t be able to purchase their own databases or digital platforms without the funding, says Tameka Lee, communications director at the Central Arkansas Library System. “Cuts could mean fewer materials and less access for communities that rely on libraries,” she says.

Be Mighty is mainly funded by the city, and to date Frazier-Emerson has not received any indication that it won’t continue to receive support.

“It’s especially important in communities that don’t have a lot of third spaces that already exist,” Frazier-Emerson says. “Access to healthy food, nutrition, and food science, [and] knowing how food works in our bodies—what we need to get through the day, ratios, protein, all that fun stuff—should be free and accessible to the public.”

The Des Moines Public Library’s Franklin branch offers the Teen Chef program, which teaches young people how to make a variety of foods, including twists on peanut butter and jelly sandwiches with different nut butters and jams, gourmet grilled cheese sandwiches, and different types of smoothies. (Photo courtesy of the Des Moines Public Library)

In the Hudson Valley, resident Lenny Sutton has seen how food can help build community and relationships. He created cookbook and supper clubs at three local libraries, which he runs each month as a volunteer, drawing from his experiences of cooking in restaurants and boarding schools for nearly 35 years.

“I’ve always enjoyed interacting with people about food,” Sutton says. “It’s a very easy way into a conversation.”

The supper clubs are freeform and encourage participants to be creative in their cooking, with monthly themes like beans, fermented foods, and cheese. He’s watched family bonding as a mother and daughter tried different recipes and learned to cook together. The club inspired one cooking aficionado to get a library card and attend other library programs.

“I’ve seen her grow with the library in a way that I’m hoping we helped facilitate,” Sutton says.

The cookbook club focuses on a single cookbook, with members preparing recipes for a group tasting and a “nitty gritty” discussion about the ingredients, recipes, and photos. Sutton relishes connecting with home cooks who want to expand their knowledge.

“I love using cookbooks as a way to peek into other chefs and their skills and where they come from.”

“I love using cookbooks as a way to peek into other chefs and their skills and where they come from,” he says.

These meaningful experiences prompted him to launch a monthly newsletter, and he maintains cookbookclubs.org, which includes meeting dates for six area groups, information about how to start a club, and suggestions for themes and events.

He sees the clubs as filling a need in a society that is less religious today. “The church potluck has been around for years and years,” he says, and adds, “Folks are looking for a way to have pieces of that [church] lifestyle that they miss or built up.”

Lopreste, in New Orleans, notes how the classes and the teaching garden—the building of a shared place together—planted real roots at the library for participants.

“When people take that amount of pride in a community space,” she says, “it truly becomes a hub of community activity amongst people, who are maybe more disparate than you would expect, to come together almost like a little library family.”

An earlier version of this story stated that in 2026, the Institute of Museum and Library Services would be eliminated. Although that is a possibility, its future has not yet been determined.

September 24, 2025

In a recent paper, University of Iowa professor Silvia Secchi finds that the current Census of Agriculture is neither complete nor accurate, and could skew federal research and investment.

January 20, 2025

September 23, 2025

September 22, 2025

September 17, 2025

September 24, 2025

September 23, 2025

September 22, 2025

Like the story?

Join the conversation.